Is Paid Maternity Leave a Right or a Privilege? Paid Maternity Leave is Healthcare and is a Human Right

Author: Bailey Logan ’26, University of Virginia

- About the Mudd Center

- People

-

Programs and Events

- 2025-2026: Taking Place: Land Use and Environmental Impact

- 2024-2025: How We Live and Die: Stories, Values, and Communities

- 2023-2024: Ethics of Design

- 2022-2023: Beneficence: Practicing an Ethics of Care

- 2021-2022: Daily Ethics: How Individual Choices and Habits Express Our Values and Shape Our World

- 2020-2021: Global Ethics in the 21st Century: Challenges and Opportunities

- 2019-2020: The Ethics of Technology

- 2018-2019: The Ethics of Identity

- 2017-2018: Equality and Difference

- 2016-2017: Markets and Morals

- 2015-2016: The Ethics of Citizenship

- 2014-2015: Race and Justice in America

- Leadership Lab

-

Mudd Undergraduate Journal of Ethics

-

Volume 10: Spring 2025

- Editorial Board

- Letter from the Editor

- Letter from the Director

- Journal AI Policy

- Selling Organs to Make Ends Meet: How Poverty Drives the Illegal Organ Trade and the Ethicality of Legalization

- Is Paid Maternity Leave a Right or a Privilege? Paid Maternity Leave is Healthcare and is a Human Right

- Psychological Coercion as Rape

- Spare Parts or Saviour Sibling? The Birth of an Ethical Dilemma

- Woman Scientist

- The Chesterfield

- In Memoriam: Chevrolet Astrovan

- The Price of Saying No

- The Right to Die: Autonomy, Ethics, and Medical Aid In Dying (MAID)

- Medicine Beyond The Hospital

- Volume 9: Spring 2024

- Volume 8: Spring 2023

- Volume 7: Spring 2022

- Volume 6: Spring 2021

- Volume 5: Spring 2020

- Volume 4: Spring 2019

- Volume 3: Spring 2018

- Volume 2: Spring 2017

- Volume 1: Spring 2016

-

Volume 10: Spring 2025

- Highlights

- Mudd Center Fellows Program

- Get Involved

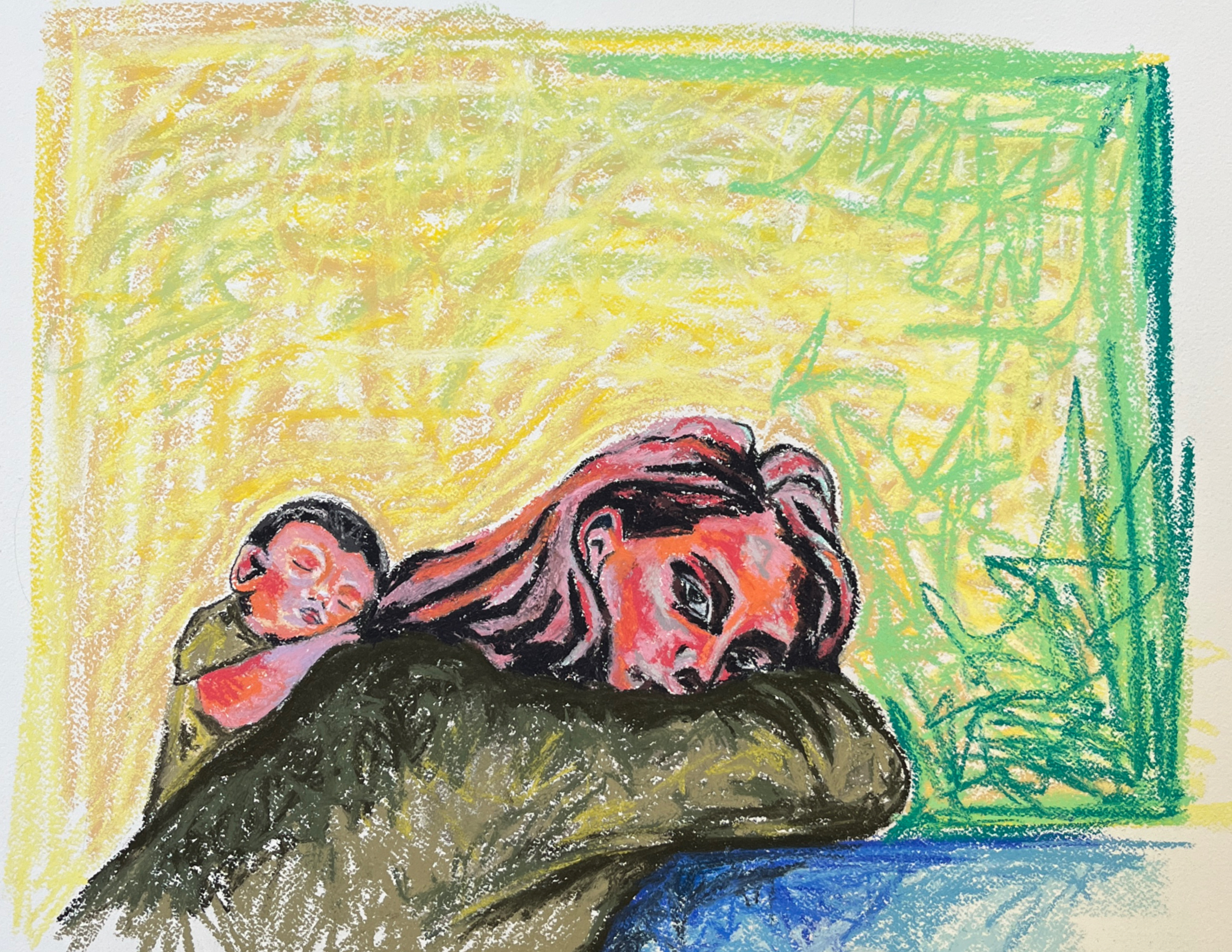

Artist Credit: Katie Lawson ’26, Washington and Lee University

Imagine enduring twenty-four hours of excruciating labor, with strong contractions that require all of your strength and resolve, culminating in the birth of a six-pound baby. Less than a week later—still bruised, bleeding, and wearing diapers—you face an impossible choice: return to your minimum wage job or stay home with your newborn, forgoing your paycheck and risking financial instability. Despite the heartbreak and the stabbing physical pain, you leave your newborn and return to work because you have no alternative. The reality is that one in four mothers return to work within ten days of giving birth because of the lack of paid maternity leave (Leigh 2020). The lack of nationally required paid maternity leave in the U.S. is unethical, placing an unrealistic physical and mental burden on women to work, sometimes in physically demanding jobs, soon after giving birth. This has been shown to contribute to postpartum depression, negatively impact the developing relationship between mother and child, and damage their physical health (U.S. Department of Labor 2009). It gets in the way of women’s ability to realize their right to health and violates all of the bioethical principles of justice, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and autonomy. Furthermore, it disproportionately impacts economically disadvantaged women as they have no option other than to return to work to financially support themselves and their newborn child. This violates a lot of ethical frameworks because it creates unequal accessibility to basic human rights.

Artist Credit: Teresa Yoon ’26, Washington and Lee University

Two major ethical perspectives that can be used to analyze current U.S. policy on maternity leave are utilitarianism and egalitarian liberalism. Utilitarianism generally judges the ethicality of something based on its consequences, trying to maximize overall benefit over overall harm (Berman, Roberts, and Reich 2008). In regard to not having mandated paid maternity leave, there is no benefit to health and in fact it is only harmful. Furthermore, the current policy is more so a result of cultural values of individualism, the relatively weak labor power, and the strong lobbying power of big businesses (Kurtzleben 2019). Therefore, in the interest of health, the good of instituting paid maternity leave far outweighs any harm to businesses in potential cost. As a result, a utilitarian ethical perspective is supportive of such a policy. Alternatively, egalitarian liberalism is another framework that can be used. This has the aim of producing fairness and equity for all. This is based on the idea that individuals have the ability to make individual choices, which can be considered negative rights. However, it also considers that this right to choose requires resources to be able to make these choices. In the context of paid maternity leave, maternity leave would be considered a choice to prioritize your health and your baby’s health. However, in order for everyone to have access to that choice, it needs to be paid. Both of these ethical perspectives favor and even require federal legislation mandating paid maternity leave (Berman, Roberts, and Reich 2008). This brings up the consideration, though, of why maternity leave is such an important choice for people to be able to make and why not being able to do so can be so harmful.

The physical toll that birth takes on the body and the recovery required are only a few of the reasons why paid maternity leave is widely accepted around the world. In addition, many women experience postpartum hormone imbalances, which can lead to a range of symptoms, including mood fluctuations. Some more specific symptoms of a vaginal delivery include vaginal and rectal pain and bruising, incontinence, bleeding, and trouble with bowel movements (Mayo Clinic Staff 2018). Another form of delivery is via cesarean section which is a major surgery after which patients will most likely have soreness around their incision and will be instructed to take the same precautions anyone would after abdominal surgery, including avoiding excessive physical activity, getting plenty of rest, not lifting anything heavy, and generally taking it easy for at least a few weeks (Mayo Clinic Staff n.d.). Both forms of delivery result in difficulty standing or being mobile for extended periods, which makes it necessary for women to rest following delivery. However, the specifics of any of these symptoms depend on the duration of delivery and whether any complications occurred (Mayo Clinic Staff 2018). These difficulties are why healthcare professionals generally recommend that women have at least six weeks of maternity leave to properly recover. However, most women still do not fully return to some form of full physical ability and hormonal equilibrium until at least six months after delivery and sometimes more. In addition, other studies have linked women taking less than eight weeks of paid maternity leave to poorer physical and mental health in the long term (Froese 2016). Maternity leave is required for the health of people who have been pregnant and have given birth immediately postpartum, but also into the future because it provides them with the time necessary for them to recover.

However, maternity leave is not just important for the person who was pregnant but also for the baby. The health of the baby is also positively correlated with paid parental leave. Babies whose parents take leave have an increased chance of being up to date on their vaccinations, being engaged in breastfeeding, securing maternal attachment, having better infant health, and displaying fewer behavioral issues (Leigh 2020). The neonatal period is a critical stage of development that sets the trajectory for the rest of their life. Putting in place federal requirements for paid maternity leave will improve the health and well-being of future generations and, therefore, enhance the development of our nation (Pinsker 2021).

Paid maternity leave is important for the emotional health of the entire family. Paid maternity leave is correlated with secure attachment between mother and child, and greater empathy and academic success for the child (Leigh 2020). Fathers or non-birthing parents who are able to take leave tend to be more involved throughout their child’s life. Parenting the child is viewed as a shared effort by both parents instead of what occurs in traditional, patriarchal families where women take on a vast majority of the child-rearing and household work (Pinsker 2021). Furthermore, the relationship between the parents is also shown to be much more stable with much lower rates of physical and emotional abuse (Leigh 2020). Having the time that paid parental leave affords is important for the emotional bonds between the parents and their child. As a result of the short-term and long-term benefits for mom and baby, it becomes clear that in order to make their health attainable, paid maternity leave is required and is healthcare.

The right to health is the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable state of complete physical and mental well-being (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2008). This idea is rooted primarily in an egalitarian liberalism framework but can also be connected to utilitarianism when it brings about a net good. There are generally two types of rights that liberalism is based on. These are positive rights and negative rights (Berman, Roberts, and Reich 2008). Negative rights are distinguished as placing no obligation on others and, in many ways, are the right to noninterference. An example of this would be the right to free speech. Alternatively, positive rights are described as the right to something like services, and, therefore, require something from others. Healthcare is generally described as a positive right, however, in reality, it is more complicated. Health is required to act in any way and live in dignity, meaning it underpins access to negative rights. So, without healthcare, an individual cannot possess their negative rights. As a result, the attainment of both negative and positive rights requires health and the provision of healthcare. Health is the most basic asset, and every person, by virtue of being human, has the right to possess it. In order for this to be possible, good quality healthcare must be accessible. Since paid maternity leave is healthcare, it is a human right and must be guaranteed for everyone (Bradley 2010).

It is important to note, though, that the idea of a right to health is not as universally held in the U.S. as it is elsewhere. However, that is primarily due to institutional structures, not a different ethical framework. When analyzing this through accepted ethical frameworks, the right to health and healthcare follows (Annas, Ruger and Ruger 2015). International policy and views on paid maternity leave starkly differ from those of the U.S. While it is somewhat of a controversial topic in the United States, around the world, 186 countries provide some form of federally mandated paid maternity leave (Pinsker 2021). Among countries that are a part of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), including Mexico, Australia, Canada, the United States, and most of Europe, the average paid maternity leave is eighteen weeks. However, the U.S .is the only country from the OECD that does not provide federally mandated paid parental leave for all, not just federal employees. The country with the longest paid leave after birth is Estonia, providing a total of eighty-five weeks. Furthermore, of the seven countries in the world that do not offer a federally guaranteed form of paid maternity leave, the U.S. is the only wealthy nation among them (Kolmar 2017). Thus, GDP does not explain this disparity, as many other nations with lower GDPs than the U.S.—like Brazil—have formed regulations (Pinsker 2021). Around the world, subsidized parental leave is considered standard and is rarely questioned, making U.S. policy and culture surrounding paid parental leave a global outlier.

There seem to be clear value differences on the right to health in the U.S. compared to the global norm. As a result, if the right to health arguments are not convincing, bioethical principles and the ethical standards of medical professionals are held very strongly in the U.S. and are also violated by the lack of nationally required paid maternity leave. This framework is known as the Georgetown Mantra, created by Beauchamp and Childress, and all four of the central bioethical principles outlined are violated by the lack of paid maternity leave (Burks n.d.). These are central principles in bioethics used to evaluate systems and situations. These four principles are nonmaleficence, beneficence, justice, and autonomy. Nonmaleficence means do no harm (Burks n.d.). Nonmaleficence is not being met in this situation, as many levels of harm are being done to women and their children in the current system. Beneficence means to do good (Burks n.d.). This is also not being met because if one is violating the rule to do no harm then one cannot be doing good. Justice, defined as ‘rendering unto each what is due,’ is not being met either. A lack of paid maternity leave shows no regard for the health, safety, or best interests of birthing people (Burks n.d.). The government is not doing its job of protecting vulnerable members of society. Finally, autonomy is also not being met because that would require the decision to return to work to be made without extreme pressure from outside factors (Burks n.d.). In this situation, many women are under extreme financial pressure to return to work and cannot afford to take a prolonged period of time off to recover. In no way do current policies on paid maternity leave adhere to any central bioethical principles and can, therefore be evaluated as unethical.

One of the main reasons that just giving women unpaid maternity leave is not enough is that this makes it only available for women with financial resources. As a result, women of lower socioeconomic classes are not able to access this form of healthcare, resulting in them and their babies having worse health overall. The impacts of having no federally mandated paid maternity leave are not felt equally by all pregnant people. Studies show that over half of Americans identify as living paycheck to paycheck, with some studies showing rates as high as 78 percent of people. These people are also not just families of lower socioeconomic status but include people of all financial means. For these families, forgoing part of their household income right after having a baby, which creates even more expenses, is not possible (Batdorf 2024). However, lower-income women still disproportionately experience the impact financially as well as suffering relatively more mental and physical health repercussions. Studies show that lower-income women are 58 percent more likely to forgo maternity leave (Kolmar 2017). Of employees who make $30,000 or less annually, 38 percent receive some form of paid leave. Juxtaposed with the fact that 74 percent of females making $75,000 or more receive paid maternity leave, one can assume there is a disparity in job benefits. Additionally, higher-income individuals may have the resources to stay home for a period of time to recover even if they are not getting paid, a possibility not afforded to their lower-income counterparts. This is especially concerning because lower-income women who give birth generally already have limited access to healthcare throughout their pregnancy and experience additional birth complications. It follows that lower-income individuals would require a longer period of time for childbirth recovery but instead receive even less time. This plays into the intergenerational health disparity based on socioeconomic class. When these women are not able to recover properly, both they and their newborns have long-term psychological and physical health impacts, which they potentially pass on to future generations (Leigh 2020).

Furthermore, many who do continue to work are paid less or given fewer opportunities to advance, as having a child is seen as a liability. This pattern is known as the motherhood penalty. This so-called penalty is exemplified by the fact that each year, women and their families lose an estimated $22.5 billion in wages after having children (Kolmar 2017). From a financial standpoint, paid parental leave creates continuity in income and employment, removes financial punishments that women experience from having children, and provides stability during this major life change (Pinsker 2021).

A human right is not something that only people who can afford it deserve; it means that all people simply because they are human deserve to have access to that right. The financial inaccessibility of unpaid maternity leave for a majority of women makes it necessary to mandate that it is paid in order to ensure that everyone’s right to health is being met. Not ensuring the right to health for all in the postpartum period does not meet egalitarian liberalism’s aim for equity in access to rights. Furthermore, as a healthcare decision, it is important that the decision to take maternity leave can be made autonomously. When women are experiencing such overwhelming financial pressures to support their family, they cannot freely make the decision to prioritize in the way necessary. In order to make this possible, the financial burden needs to be relieved so the decision can be made autonomously.

While the argument in favor of nationally mandated paid maternity leave is strong in terms of the benefits for individual women, their children, and their families, there is also a strong argument for the societal benefit (Arneson 2021). As a country, we require women to work in order to sustain our economy and to have children to sustain our population. The workforce of the United States requires women in order to maintain their economic standing in the world and requires women to bear the children of the next generation, which will also be the workforce of the next generation (Arneson 2021). Societies of countries that have federally imposed mandatory paid maternity leave experience tangible benefits, including increased economic productivity, which the U.S. is currently overlooking. Furthermore, in order to remain respectable on the world stage as a country that protects the human rights of its citizens, it is important that the U.S. takes these steps to ensure the right to health of every citizen, upholding central bioethical principles that underlie the entire medical system.

Paid maternity leave required by the federal government serves the interest of the physical, mental, and financial health of the women giving birth, their children, and their families. Maternity leave is not a vacation or a luxury but a human right necessary for recovering from the birth process and for nurturing the next generation of the population. While staunch adversaries of paid maternity leave posit that it is financially impossible, many countries with lower GDPs already ensure that women have access to this right. Ethically, for the birthing people, their children, and society, the only choice is to prioritize women’s health and women’s rights and to pass legislation to require paid maternity leave for all in the United States. Women should not be ashamed to have families or prevented from having a career. Women deserve to be treated with dignity and respect. Women deserve to have time to recover after giving birth without fear of repercussions.

References

Arneson, Krystin. 2021. “Why Doesn’t the US Have Mandated Paid Maternity Leave?” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210624-why-doesnt-the-us-have-mandated-paid-maternity-leave.

Bayefsky, Anne F. 2000. “Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.” In The UN Human Rights Treaty System in the 21 Century, edited by Anne Bayefsky, 451–58. Brill | Nijhoff. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004502758_044.

Bradley, Andrew. 2010. “Positive Rights, Negative Rights and Health Care.” Journal of Medical Ethics 36 (12): 838–41.

Burks, Douglas J. n.d. “Beauchamp and Childress: The Four Principles.”

Froese, Monica. 2023. “Maternity Leave in the United States: Facts You Need to Know.” Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/pregnancy/united-states-maternity-leave-facts.

Kolmar, Chris. 2023. “Average Paid Maternity Leave in the US [2023]: US Maternity Leave Statistics.” Zippia (blog). https://www.zippia.com/advice/average-paid-maternity-leave/.

Kurtzleben, Danielle. 2015. “Lots of Other Countries Mandate Paid Leave. Why Not the U.S.?” NPR It’s All Politics. https://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2015/07/15/422957640/lots-of-other-countries-mandate-paid-leave-why-not-the-us.

Leigh, Suzanne. 2020. “National Paid Maternity Leave Makes Sense for Mothers, Babies and Maybe the Economy | UC San Francisco”. https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2020/03/416831/national-paid-maternity-leave-makes-sense-mothers-babies-and-maybe-economy.

Mayo Clinic Staff. 2023. “What You Can Expect after a Vaginal Delivery.” Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/postpartum-care/art-20047233.

Mayo Clinic Staff. 2024. “Changes to Expect after a C-Section.” Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/c-section-recovery/art-20047310.

Pinsker, Joe. 2021. “Parental Leave Is American Exceptionalism at Its Bleakest.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/11/us-paid-family-parental-leave-congress-bill/620660/.

Roberts, Marc J., William Hsiao, Peter Berman, and Michael R. Reich. 2008. Getting Health Reform Right: A Guide to Improving Performance and Equity. Edited by Marc Roberts, William Hsiao, Peter Berman, and Michael Reich. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195371505.003.0001.

Ruger, Jennifer Prah, Theodore W. Ruger, and George J. Annas. 2015. “The Elusive Right to Health Care under U.S. Law.” New England Journal of Medicine 372 (26): 2558–63. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhle1412262.

U.S. Department of Labor. 2009. “Family and Medical Leave (FMLA).” DOL. https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/benefits-leave/fmla.

The views, opinions, and conclusions expressed in student-authored works published [in this journal / on this website] are those of their respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or views of Washington and Lee University or the Mudd Center or its administrators, faculty, or staff.

- About the Mudd Center

- People

- Programs and Events

- Leadership Lab

-

Mudd Undergraduate Journal of Ethics

-

Volume 10: Spring 2025

- Editorial Board

- Letter from the Editor

- Letter from the Director

- Journal AI Policy

- Selling Organs to Make Ends Meet: How Poverty Drives the Illegal Organ Trade and the Ethicality of Legalization

- Is Paid Maternity Leave a Right or a Privilege? Paid Maternity Leave is Healthcare and is a Human Right

- Psychological Coercion as Rape

- Spare Parts or Saviour Sibling? The Birth of an Ethical Dilemma

- Woman Scientist

- The Chesterfield

- In Memoriam: Chevrolet Astrovan

- The Price of Saying No

- The Right to Die: Autonomy, Ethics, and Medical Aid In Dying (MAID)

- Medicine Beyond The Hospital

- Volume 9: Spring 2024

- Volume 8: Spring 2023

- Volume 7: Spring 2022

- Volume 6: Spring 2021

- Volume 5: Spring 2020

- Volume 4: Spring 2019

- Volume 3: Spring 2018

- Volume 2: Spring 2017

- Volume 1: Spring 2016

-

Volume 10: Spring 2025

- Highlights

- Mudd Center Fellows Program

- Get Involved

The Mudd Center

-

Washington and Lee University

209 Mattingly House

Lexington, VA 24450